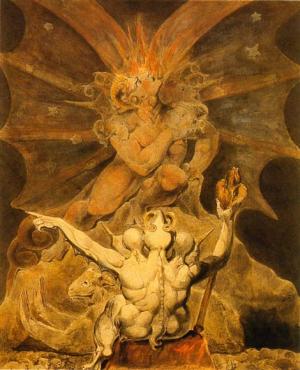

The Tate Britain is to recreate that William Blake’s first and only exhibition – exactly 200 years after it was staged in 1809 – and will bring together at least nine of the surviving 11 works from the 16 in the original show. It will also republish Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue, now regarded as a fascinating and significant commentary on the London artworld of his day. The 1809 exhibition, held in his brother’s Soho hosiery shop in Golden Square, Soho, proved a turning point in the artist’s career. The paintings, according to the only critic who bothered to review the show, were wretched and the artist suffered from “the wild effusions of a distempered brain”. Embittered by its appalling reception, he withdrew even more from the art world into solitary eccentricity.

Most Blake exhibitions have always tended to focus on the illuminated books. But this exhibition shows us Blake as he wanted to be seen. The image Blake wanted to project in that 1809 exhibition was of an ambitious public painter of historical and religious subjects, who yearned to sweep away what he regarded as a venal and corrupt art world – rather than of the quintessential outsider, as he is thought of now.

Blake was a Christian who sought to bring out the religion’s repressed prophetic side. This meant sympathising with revolutionary politics, even when such thought was atheist. Above all it meant rejecting all forms of institutional church. This is the real heart of Blake’s radicalism: the insistence that Christianity is meant to be free of institutional control.

The message throughout his work is that the true religious vision is inimical to the established church, to all organised religion and all orthodoxy. He announced a new era of direct communion with God. The notion of a divine principle in everyone was the basis of his concept of Imagination. This higher form of perception was by means of art, not science. The core belief was that Christianity was the true religion of humanity, of world-affirmation and of freedom. He saw Christianity as a religion of liberty and utopian love. He sometimes seems to advocate free love, the abolition of all moral constraints.

Blake’s father was an industrious London tradesman, who sent him to drawing school when he was ten and apprenticed him to James Basire, a well-known engraver, five years later. Blake was to remain an engraver for the rest of his life, subsidising his experimental work with his commercial income. Engravers were viewed as skilled workers rather than artists and, for a long time, could not be members of the Royal Academy because that was, according to its documents, “incompatible with justice and a due regard to the dignity of the Royal Academy”. When Blake was finally admitted, he called them “a pack of Idle Sycophants”. He reserved particular venom for Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the Academy, saying, “This man has been hired to depress Art”. He saw the Academy’s training system, based on the copying of classical statues and paintings, as suppressing imagination. He felt the whole system was tied up with patronage and “where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on, but war only”.

Blake died on August 12, 1827, and was buried in an unmarked grave in the dissenters’ graveyard at Bunhill Fields, East London. In the years that followed his death only a handful of friends, pupils and followers kept his memory alive. When the Pre-Raphaelite movement came to prominence Blake became fashionable.

The consequence was the creation of a Blake cult and the uprising of a number of ardent collectors of his books, his engravings, and such of his rare drawings and pictures as happened to come into the market; exhibitions were held at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, at Boston, and elsewhere; several editions of his poems were published, and books were ‘written about his mystical art in. England and in Germany.

According to Gilchrist, his biographer, Blake was well versed in the doctrines of the Gnostics, and his own personal mythology contains many points of cohesion with several Gnostic myth themes (for example, the Blakean figure of Urizen bears many resemblances to the Gnostic Demiurge). However, efforts to dub Blake a “Gnostic” have been complicated by the complex nature and colossal extent of Blake’s own mythology, and the variety of myths and themes that are referred to as “Gnostic”; thus, the exact relationship between Blake and the Gnostics remains a point of scholarly contention, though a comparison of the two often reveals intriguing points of correspondence.

To Blake indeed the facts were nothing, except as ground-works for his famous “Visions”, which he regarded it as his duty and privilege to translate into line and colour for the enlightenment of the world.

William Blake Retrospective – Tate Gallery…

The Tate Britain is to recreate that William Blake’s first and only exhibitio……